This weekend Harlean (who is a fiction) and I had a really fun photo shoot. We were using our Lensbaby gizmos for the first time, and allowed ourselves the emotional room to experiment and accept when things didn’t work right, and celebrate when changing something actually had the predicted result. A wonderful day in the studio.

There is a part of me that believes that getting good results with your current gear is an indication that you don’t need better gear. But over the years I have identified a few cases where new gear would be better. And heck, I used to watch a series on YouTube that included “Good Photographer, Shitty Camera” episodes where respected pros would be handed a Barbie doll with a camera embedded in her chest or a LEGO camera or what-have-you, and invariably these pros would manage to find a remarkable image.

But none of them said, “I’m ditching my Nikon for Barbie!” Sure, some of those folks are probably still using Canon 5D Mark III’s, but I suspect not many of those do a lot of self-portraits. Here in this house the limitations of the 5D started to become apparent when self-portraiture became a regular occurrence. On the 5D, you have to make choices — not all autofocus modes work when you are using strobes or speedlights. Specifically, the autofocus modes that don’t require you to look through the viewfinder are absent. Additionally, the presence of the viewfinder itself can interfere with autofocus, as light coming in through the viewfinder can confuse things.

### For a bit here, I go on about Camera Stuff that is interesting (to me) and relevant(ish), but does not really build on the narrative of this episode. You could probably skip to the picture below if you’re not interested in the evolution of modern cameras or how that solves specific problems in our studio.

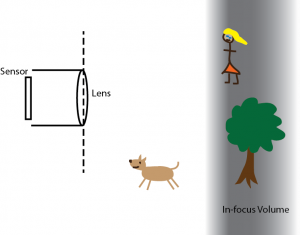

Anyway, at the heart of those problems is the very nature of the SLR itself. SLR stands for “Single-Lens Reflex” and is a system where there is a mirror in the camera that while at rest diverts the light coming through the lens up to the viewfinder. When you push the shutter button, the mirror snaps up out of the way and the light hits the sensor (or film) instead. It is the mirror snapping up and back that gives an SLR its distinctive shutter sound.

The reason some focus modes aren’t always available in our 5DIII is that those focus settings require computer processing to identify eyes, faces, and whatnot, and when the light is going to the viewfinder rather than hitting the sensor, that processing cannot take place. There is a mode that lifts the mirror to allow that processing, but then the camera can’t trigger the flash for “electronic shutter” reasons I don’t quite understand.

SLR was a big deal because it gave the photographer a much better idea what the picture was going to be like. Before that, the viewfinder had its own lenses, which tried really hard to match what the main lens would show, but as the “main lens” became ever more complicated, that became impractical.

But your phone doesn’t have a mirror in it, now does it? The light doesn’t need to be diverted to a viewfinder, the sensor chip itself sends that info to a screen. Then when you push the “shutter”, it sends a signal to the camera to take a much higher quality image off the same sensor and send off for storage.

All the big camera companies have lines of “digicams” that try to be better than a phone and easy to carry around and shoot with. They have the screen on the back, and depending on where you live, they might be legally required to play a recording of that SLR mirror-clack when they take a picture.

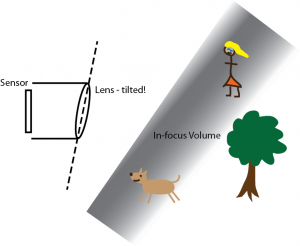

But until fairly recently, all the high-end gear continued to be SLR. Honestly, I know there were compelling reasons, but I’m not entirely sure what they were. But then Fuji and Sony made exciting high-end “mirrorless” cameras. As mentioned above, “mirrorless” itself wasn’t huge news, but now that word is used to describe the top-end gear out there that doesn’t have a mirror.

Canon responded with a thud, creating the EOS-M format, that utterly failed to establish them in this market. Maybe not a Zune-level flop, but in the neighborhood. Nikon did a little better, and Sony pulled ahead while Fuji found a very comfortable niche to totally dominate, while still pushing Sony.

Now, Canon and Nikon have stepped up their games, and Canon at least burned their boats on the shore. There will be no new major updates with a mirror from Canon, and no new lenses to fit their SLR line. It’s all about the R.

With that long-winded explanation, you might not have noticed that a mirrorless camera solves two of our current issues: “Aha! No optical viewfinder means no light leaking in from the eyepiece to mess up autofocus!” and (less obvious) “Aha! There’s no mirror! Sensor-based focus modes are available all the time!”

So, after one very frustrating shoot that might have been somewhat less frustrating with different technology, and two very smooth shoots to prove we deserved it, we helped pay off Canon’s gamble:

It is physically smaller than the 5D it is replacing, because there’s no need to make room for a mirror to flip up and back. The geometry of the mount means that lens makers can go crazy. Hopefully, somewhere at Canon is that troublemaker saying, “hey, remember when we did that 50mm f/1.0? We can beat that.”

So there it sits, radiating potential. In the camera world, as in computers, the chips are obsolete before they even land on your doorstep. I’m honestly surprised that the 5DIII is still not obsolete after eight years. But in photography the real investment is in the lenses. Camera bodies come and go, but glass is forever. Mostly. There are better versions of almost every lens I own made specifically for the new camera, but not enough better to justify replacement.

All one needs is an adapter to connect the old EF-mount lenses to the new RF body. (In fact, because of the new geometry, I can now attach other, non-Canon lenses I’ve long longed over. There’s a Minolta…)

Anyway, all I need is an adapter, and my library of lenses will be ready to go. That’s all I need.

The adapter is on backorder. Sitting in a box is a pretty dang incredible camera, and I can’t attach any of my lenses to it. The L-plate arrived today, so I have a lot of flexibility attaching the new camera to a tripod. Just… no lenses. I can hold it, I can admire it, but I can’t take any pictures with it. “Coming soon!” the reputable camera company says.

Not soon enough.