Where to start, where to start. My longest ride ever? The things I saw? The nearly-endless interval sitting on the concrete, my legs stretching out into the sun, in emotional and medical shock, staring at my water bottle lying in the middle of the sidewalk as I reconciled myself with never seeing my bike again? The stunned disbelief as two strangers brought my bike back to me?

I’ll start with water. I drink a lot of water, even when siting in an air-conditioned office. I have convinced myself that my second-biggest obstacle to climbing my mountain (It’s not “Mt. Hamilton” anymore, it’s My Mountain) is water. Unless I pull a trailer with one of those big ol’ coolers behind me, I’m going to have to find ways to replenish on the climb.

So, I’ve started to be more conscious of the places water is available, even on my more modest routes. Trying to get it into my rather thick skull that’s it’s ok to load up at any opportunity. (I do not know if there will be opportunities on my mountain.)

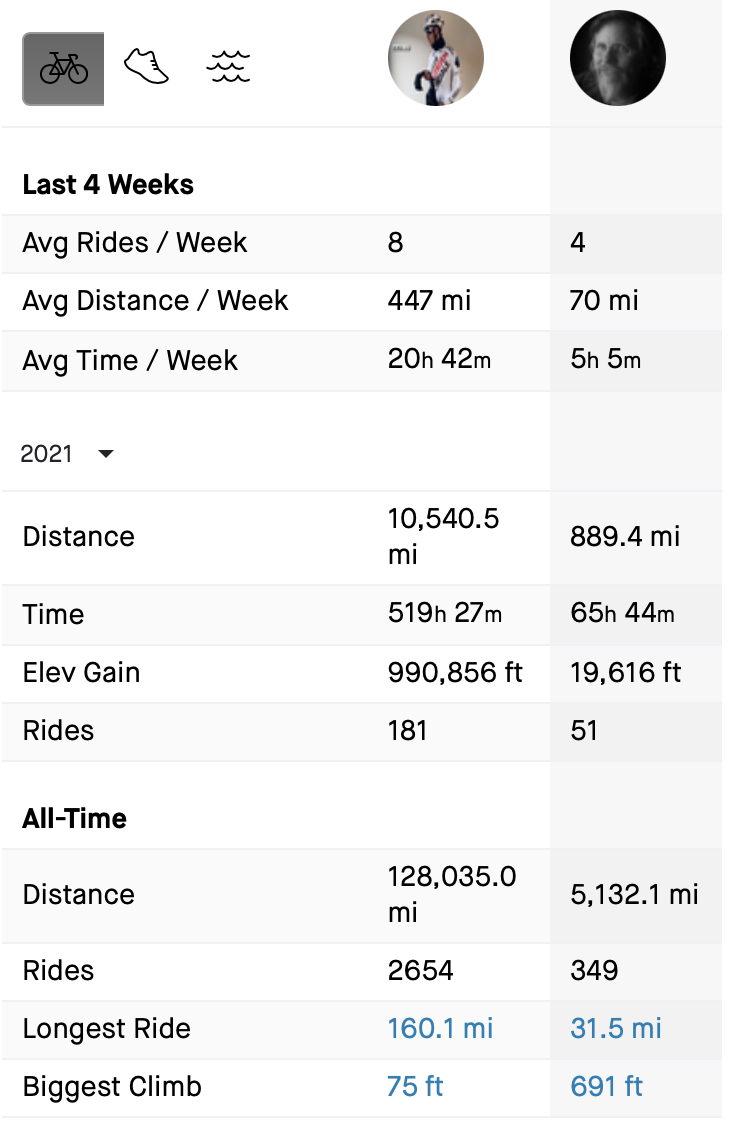

Eight days ago I set out on a ride, not sure exactly where I would go, but confident there would be a lot of miles. I knew when I was done that Strava would congratulate me on my longest ride ever, and I was looking forward to that pat on the back. Machines are notoriously free with their validation, but some machines are more worth impressing than others.

So a long ride north exploring what is intended to be a bicycle artery, which is really well done except for two stretches that are terrible. I was on roads I didn’t know, and the sun was straight overhead, but I knew I was going the right direction by the headwind. If you’re riding into the teeth of the wind, you’re traveling roughly parallel to the runway at SJC. I hate headwinds, but this one at least I know will pay me back when I was heading home on weary legs.

But… all this riding around isn’t what I teased above. I was a good ride. I found some cool things I will have to explore again. I made my way over to Alviso and began my tailwind ride home south on Guadalupe River Trail.

The trail includes a stretch of roughly ten miles with no interruptions — no traffic signals, no cross streets — that you just cruise and enjoy. But when I got to the south end of that, thirty miles into my ride, I had consumed all the water in my big bottle and the Gatorade I put in the second holder as well.

By now, I was not far from home. I could have made it without too much discomfort. But I told myself that I needed to start to get used to finding water on the trail if I planned to do longer rides. So, just for practice, I stopped at a little park to fill up my water bottle. This may seem like a strange thing to practice, but for me “stop pedaling for two minutes so you don’t die later” is not as simple as all that.

So I stopped for water. It was at a little park with public restroom made out of the same brown faux-stone that all public restrooms are made of in all city parks west of the Mississippi. There were people outside as I rode past, so I guessed that the covid water shutdowns had been canceled. I would fill my bottle. I doubled back.

The park is separated from the street and the sidewalk by a low metal fence – not a barrier In any real sense, but a symbolic demarcation. As I rolled through the gate into the park and turned back toward the water, I decided I didn’t trust the people hanging out there so much, so rather than leave my bike near them, I leaned it against the fence, a few feet away.

That was a very bad decision.

I said hello to the couple standing in the shade of the restroom blok. He was, let there be no doubt, a fan of the Oakland A’s; he was garbed in yellow and green from neck to toe, with plenty of logos. She was dressed for the summer heat, a light top but still blue jeans.

This next bit is hard to tell, because of how stupid I was. The drinking fountains on the outside of the building didn’t work. “The taps work inside,” the A’s fan said.

It would only take a moment. Pop in, fill the bottle, back out. Just a few seconds. I went in, and for five seconds of increasing anxiety I tried to make water come from the spigot, alll the while thinking “my bike is out there” and finally dashing back out, in time to see a stranger reach over and hoist my bike over the fence.

“NO!” I shouted. “No! No! No!” And I started to run after him.

An aside here, and an important one. Many times I have told myself that in a situation like this, I would do my best to be a witness, not a hero. Be smart. Really look at the person, so that in court I can be confident. Get the details. Consolidate them before lawyer questions can shake them. I failed at this. Absolutely flunked the course. I chased, vaulting the little fence and still shouting. Maybe a shitty mustache? When talking to the police I was also able to offer that he was wearing long pants, which seriously narrows the suspect list.

Instead I was a hero. I chased the guy, vaulting the fence in what might have ben an impressive maneuver. But I was in bike shoes (SPD so better for sprinting after bike thieves than others) and after about five strides past the vault I knew my left leg was blown. Still I was not being a good witness. My eyes were on my bike, the rear safety light still blinking. A folding knife dropped out of the thief’s pocket as he rode away. He headed South and took the first turn to the east and he was gone.

I staggered forward far enough to collect the knife (carefully – fingerprints, after all) then limped back to where my witnesses were standing. They asked If I was OK, and told them that actually I was not. “Do you know that guy? I asked.

“I know him, but I haven’t seen him around for a while,” the guy answered.

I will not reproduce the entire conversation, but as they assessed the damage I had taken, and my long white beard, the woman said, “do you want us to go after him?”

I heard that as “can we sound helpful and leave?” but I answered “If you really think you can find him, then yeah, sure.” And they left.

I’ll fast-wind ahead through remembering my watch is also a phone and calling The Official Sweetie of Muddled Ramblings and Half-Baked Ideas and calling the police and sitting, staring at my water bottle which I had carried at least long enough that it was on the street side of the fence, the lid a few feet farther along, in the shade of a tree that was small enough to only be a promise of a future idyllic neighborhood. My head started to spin, and I laboriously stood only to cling to the damn brown brick so I wouldn’t fall over again. I was not in a good way.

And then there they were. With my bike. With my fucking bike.

“I’m so glad you’re still here!” she said, huffing and flushed with the effort of a quick ride. “I was worried if you were gone we’d never find you.”

There were some moments of joy and simple gratitude that followed, snd she (and he, to a lesser extent) seemed of a mind to chat. “He was heading for the labyrinth,” she said. “It’s a place they sell stolen bikes. But he took a wrong turn.” The labyrinth is well-named. “When we found him, he was looking at the back gears and having a hard time.”

“This bike shifts differently,” I said, and she laughed. We talked about the bike for a bit, about how this outfit in Utah was making great bikes. I opened the pouch on my bike that also held my wallet, and was happy to find some cash inside, that I keep in reserve for waitstaff. I offered it to her.

“You don’t have to,” she said. Twice, before taking the money. It was fifty dollars. In this city, that’s not much.

In our conversation, she proudly proclaimed that they had paid for their bicycles. But I haven’t mentioned that the two of them had three bikes, and both were skilled at “ghost riding”: pedaling one bike while pulling along another. It’s an important skill for bike thieves. She also said “I offered him this bike in exchange, but he just gave me yours back.” For her, bicycles are generally fungible. My bike was unique, which made it more dangerous, but also I was a graybeard with a blown leg who clearly didn’t know how to deal, and I think it was that more than anything else that led to my happy reunion.

I mentioned to them that I had managed to call the police, and he said with a laugh. “I’m no interested in talking to them.” and she laughed too and they rode away with their three bicycles.

I am not angry, not even at the asshole who snatched my bike and rode away. There is a world of necessity that festers in our cities, a world invisible to the Uber class. On my favorite ride I pass a camp filled with chickens and stolen bicycles. This is not big-time organized crime, it’s people struggling to survive. They’re living in tents for crying out loud. The underground economy of stolen bicycles is not the disease, it is a symptom of a deeper ill.

So, I lied, actually. I am angry. I am angry at a nation where people eating too much is a major health crisis while we also have kids gong hungry. I am angry at a nation where the homeless problem is solved by making them go somewhere else. We have enough. We have enough to put a roof over every head. We have enough to put food in every belly. But we don’t. Honestly, we don’t even try.

I rode home, slowly, on my own bike, pedaling with a very unhappy leg — a person of privilege who had somehow found sympathy from people who have far less than I do. I will pay that back.

10

10

Sharing improves humanity: