Suspension of disbelief is an important part of fiction. As fiction, a story is inherently unreal, and the reader knows it. Yet the reader is willing to pretend for a while that the events in the story could or even did happen. Readers become like the Thurmians in Galaxy Quest — treating the story as if it were a historical document.

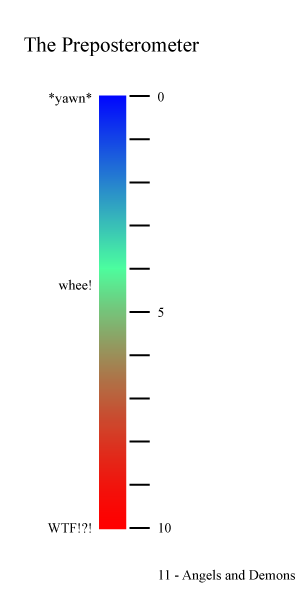

Yet some stories make that nearly impossible to do. They cross the line from incredible to preposterous, and the story is broken. Enter the Preposterometer, a tool for rating just how far credulity must be bent to stay in the novel.

The rules for the preposterometer are not simple. For instance, some genres of literature have long-accepted preposterous ideas that the reading community has decided to overlook. In Science Fiction, a writer can travel faster than light and ignore the relativistic consequences. Physically, that’s preposterous, and to base an entire novel on it would break everything if the reader insisted that science fiction conform to science. But faster-than-light travel is fun, and everyone does it, and so we have culturally pushed that problem way down on the preposterometer scale. For science fiction, the preposterous is acceptable as long as it’s consistent.

Every genre, even literary fiction, has it’s culturally-acceptable preposterosities. Literary Fiction has the exquisite coincidence and the inexplicable connections between people (I just made those terms up). I was about to say that the only preposterosity that is unforgivable across genres is human nature – people still have to behave like people. Even aliens have to behave like people most of the time. In my poor, negelected novel The Monster Within the part that recieved the most critical feedback was when two characters who did not get off to a good start together became friends rather abruptly. Magic? Sure, no problem, but don’t let Hunter be such a pushover. It wasn’t realistic.

Romance novels might be the exception to that. There is a specially-modified range of human responses that only applies in Romance-world, where (for instance) sex with the right woman can transform a rogue into a protector. Preposterous? Of course. Acceptable? Absolutely.

So, then, when measuring a story on the preposterometer, context matters. Internal consistency matters. How the preposterous event is set up matters a great deal.

A little preposterosity (such a better word than ‘preposterousness’, though I’m still debating the spelling with myself) is good for a story. We have a word for stories where nothing unusual or amazing happens. We call them ‘boring’, or perhaps ‘blog entries’. So as we undertake to rank stories on the preposterometer, we must recognize that scoring a zero is at least as bad as scoring a ten. Somewhere in the middle is a happy, believable-yet-enjoyable range of preposterosity that turns a story into a good yarn.

It’s also worth noting that humor and satire are almost expected to push the preposterometer into the red. That’s why we have the phrase “so bad it’s funny.” So-called serious stories that over-preposterate wind up as humor quite by accident. (Not always — sometimes they’re just bad.) I’ve been thinking about my story Quest for the Important Thing to Defeat the Evil Guy, and I don’t think it’s preposterous enough yet. When you’re parodying an inherently preposterous genre, you really have to pull out all the stops.

Here is a rough sketch of the preposterometer, but it’s not in a useful form yet. What’s lacking is a benchmark for the various levels. (Do we need a separate benchmark for each genre?) While I have plenty of ideas for the middle- and upper-preposterous benchmarks, I couldn’t come up with examples off the top of my head for the low-preposterosity examples. I’ll keep working on fleshing out the scale, but any suggestions you have would be welcome. Spread the word! Together we can quantify this elusive metric.

Actually, even in romance novels, the level of preposterousity that you cite would be unacceptable. In a good romance novel, humans must still behave in human ways, and sleeping with the heroine will not instantly turn the rogue into a protector. There will be some character development, both before and after, of which sleeping with the woman is a stage along the way. I’m drawing a blank right now on the title, but there’s one by M.M. Kaye set in Zanzibar that gets everything just right.

That said, I have seen some bad romance novels that do get up to an 8 or 9 on the scale. I don’t like those.

In addition to humans not acting human enough, in science fiction, I often have problems with aliens not acting alien enough. For example, in C.J. Cherryh’s Chanur series the main characters really seem to be just humans dressed in cat fur, rather than an alien race; the characters seem to be purely and completely human to the point that I forget they’re really sapient cats until a reference to claws or a tail catches me by surprise.

As for the low end of the preposterometer, that’s where a lot of historical fiction would fall. For one thing, the fans of historical fiction absolutely INSIST on historical accuracy, and, I have been told be an acquaintance who writes historical fiction, they LEAP on any inaccuracies and inconsistencies in the book. She spends more time doing research than actually writing to keep up to her fans’ standards. So where matters of historical fact are concerned, historical fiction will be scrupulously accurate. Of course, you still have the issue that the characters have to be believable, and the plot has to be interesting. Check out Patrick O’Brien’s Master and Commander series for examples of keeping a balance between accuracy and interestingness.

I think Die hard II clocks in at a 10 on the preposterometer. So far beyond belief that it makes you want to smack your head with a brick.

I ought also to mention the Sharpe’s Rifles series by Bernard Cornwell as excellent historical fiction. I find those novels extremely satisfying.

Meanwhile, the basic television daytime drama, aka soap opera, probably weighs in somewhere between 7 and 8. I find one good for creating an hour in my day to be totally brainless.

I wrote a lengthy defense of Dan Brown here and then deleted it. I just couldn’t get the tone right, and I feared coming across as offending and not being able to convey the respect in “With all due respect…”

Suffice to say, I enjoy Dan Brown books. Really liked Da Vinci code. But I hear and acknowledge and respect your disagreement.

I suspect that there are more people who would agree with you than with me, if his popularity is any measure.

It’s easy to come off as argumentative in a forum like this, rather than debatative, which is why emoticons were invented. Perhaps if the world hadn’t rushed to turn them into little cutsie cartoons they would have become part of serious online communication.

Three perfect examples for this topic!

Carol Anne’s suggestion of the excellent Sharpe’s series reflects author Bernard Cornwell’s efforts to keep them from rising too high on the Preposterometer. That’s no easy task when a hero bests dozens of foes in combat AND appears at every major battle of the British campaign against Napoleon.

Cornwell’s trick seems to be giving Sharpe a little bit of luck at a time, in place of any one impossible feat, as in, say Dan Brown’s Angels and Demons.

If you could stomach the book through to the climax, you’d find the hero survives a leap from a helicopter at 10,000 feet by holding onto the corners of a folded tarp and using it steer his way down to a river. I couldn’t stomach paying for the movie as well, but they surely modified that scene to make it less laughable.

Sure, it’s fun to read something light and entertaining now and then, just as it’s fun to watch, say, Hunt for Red October. It was like Die Hard II, without breaking the Preposterometer.