Suspension of disbelief is an important part of fiction. As fiction, a story is inherently unreal, and the reader knows it. Yet the reader is willing to pretend for a while that the events in the story could or even did happen. Readers become like the Thurmians in Galaxy Quest — treating the story as if it were a historical document.

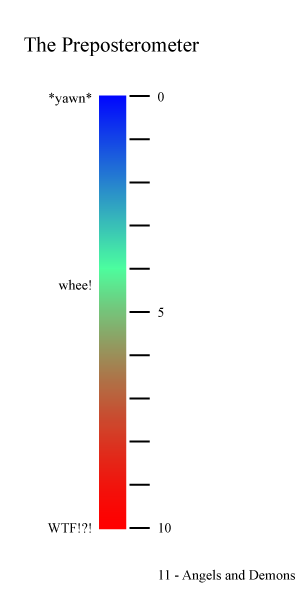

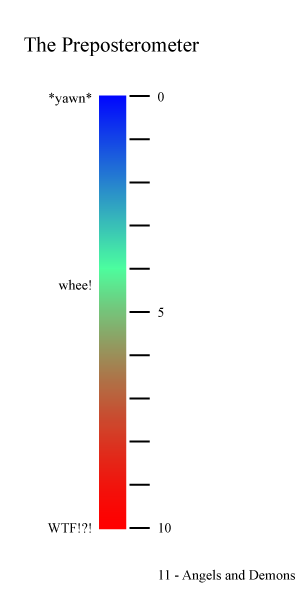

Yet some stories make that nearly impossible to do. They cross the line from incredible to preposterous, and the story is broken. Enter the Preposterometer, a tool for rating just how far credulity must be bent to stay in the novel.

The rules for the preposterometer are not simple. For instance, some genres of literature have long-accepted preposterous ideas that the reading community has decided to overlook. In Science Fiction, a writer can travel faster than light and ignore the relativistic consequences. Physically, that’s preposterous, and to base an entire novel on it would break everything if the reader insisted that science fiction conform to science. But faster-than-light travel is fun, and everyone does it, and so we have culturally pushed that problem way down on the preposterometer scale. For science fiction, the preposterous is acceptable as long as it’s consistent.

Every genre, even literary fiction, has it’s culturally-acceptable preposterosities. Literary Fiction has the exquisite coincidence and the inexplicable connections between people (I just made those terms up). I was about to say that the only preposterosity that is unforgivable across genres is human nature – people still have to behave like people. Even aliens have to behave like people most of the time. In my poor, negelected novel The Monster Within the part that recieved the most critical feedback was when two characters who did not get off to a good start together became friends rather abruptly. Magic? Sure, no problem, but don’t let Hunter be such a pushover. It wasn’t realistic.

Romance novels might be the exception to that. There is a specially-modified range of human responses that only applies in Romance-world, where (for instance) sex with the right woman can transform a rogue into a protector. Preposterous? Of course. Acceptable? Absolutely.

So, then, when measuring a story on the preposterometer, context matters. Internal consistency matters. How the preposterous event is set up matters a great deal.

A little preposterosity (such a better word than ‘preposterousness’, though I’m still debating the spelling with myself) is good for a story. We have a word for stories where nothing unusual or amazing happens. We call them ‘boring’, or perhaps ‘blog entries’. So as we undertake to rank stories on the preposterometer, we must recognize that scoring a zero is at least as bad as scoring a ten. Somewhere in the middle is a happy, believable-yet-enjoyable range of preposterosity that turns a story into a good yarn.

It’s also worth noting that humor and satire are almost expected to push the preposterometer into the red. That’s why we have the phrase “so bad it’s funny.” So-called serious stories that over-preposterate wind up as humor quite by accident. (Not always — sometimes they’re just bad.) I’ve been thinking about my story Quest for the Important Thing to Defeat the Evil Guy, and I don’t think it’s preposterous enough yet. When you’re parodying an inherently preposterous genre, you really have to pull out all the stops.

Here is a rough sketch of the preposterometer, but it’s not in a useful form yet. What’s lacking is a benchmark for the various levels. (Do we need a separate benchmark for each genre?) While I have plenty of ideas for the middle- and upper-preposterous benchmarks, I couldn’t come up with examples off the top of my head for the low-preposterosity examples. I’ll keep working on fleshing out the scale, but any suggestions you have would be welcome. Spread the word! Together we can quantify this elusive metric.

1

1

Sharing improves humanity: