When considering whether to buy a “vintage” lens to put on a modern camera body, there are a few things to consider:

1) Will it work at all?

2) Assuming it works, what lens should I get?

3) How do I take good pictures with this thing?

This episode is to answer question 1. It’s the simplest.

When electronic auto-focus was invented, camera and lens manufacturers rushed to produce systems that took advantage of the technology. The lenses weren’t necessarily optically better, but they were a heck of a lot more convenient. Nowadays, auto-focus performance is one of the things lenses and cameras are graded on, and it can allow photographers to get shots they never would have before. Cameras can actually track a moving object and keep the focus on it.

But what became of all those old manual-focus lenses?

They’re still out there, sitting in closets and gathering dust in pawn shops, forgotten. And while optical and manufacturing technology has advanced in the last few decades, there are some very nice lenses that can be had for a very good price.

But before you go diving through eBay, scratching your head over Russian-made bargains and obscure Japanese masterpieces, there are a few fundamental questions you need to answer. The most important is, “Will this lens work on my camera?”

The question is pretty simple to answer, but first there are a few things you need to understand. They aren’t complicated, so pretty quickly you will be able to build a list of which lens mounts work for you.

A brief aside: The answer to the question “Can I make this work on my camera?” is always yes. You can find a way. HOWEVER, some lenses will require an adapter that has yet more lenses in it, which will cost a lot and impact the quality of the photo. So I’m concentrating here on simple mechanical adapters that don’t have any glass elements themselves.

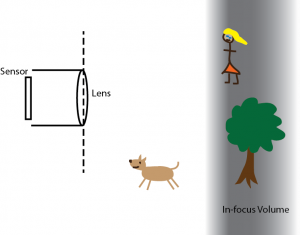

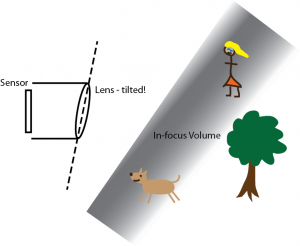

Most of the “will it fit?” answer is simple geometry. Each lens is designed to fit on a hole on the front of a camera. The two key measurements of that hole are how big it is, and how far from the film or the sensor the hole is. If the lens expects a smaller hole than the one on the front of your camera, no problem. If it needs a bigger hole, you’re out of luck — you can’t enlarge the hole in the front of your camera without a saw.

Similarly, the lens expects to be a certain distance from the film (this is often called the flange distance or register). If your lens expects to be farther from the sensor, that’s fine; the adapter can push it farther back. If it needs to be closer, then even if you find an adapter the lens is going to be poking down into the guts of your camera, which is not good.

There is a tricky range where the lens expects to be just a tiny bit farther from the film, and in this range, though it’s theoretically possible to make an adapter, the adapter would have to be so thin it’s not practical to manufacture.

For example, my camera body has a Canon EF mount. The flange distance is 44.00mm, and the diameter is a mighty 54mm. I can safely assume that it will be easy to mount any lens that expects to be 45mm or farther from the camera, and needs a hole less than 54mm. There is a range between 44 and 45mm that is dicey; the metal used to make the adapter has to be extremely thin. (That’s too bad, because There’s a Minolta lens at 44.5 that I really want. It’s a magical lens, a lens that literally* redefines bokeh.)

You don’t have to go through the will-it-fit calculation every time, of course. I happen to know that old lenses with the very-common M42 mount work just fine on my camera with an adapter that costs maybe $5 or less. Therefore one of my common eBay search terms is “M42”. Here is a list with many of the mounts you will encounter. If you shoot with a Canon EF, the size of the hole is never an issue (the EF hole is very large), so this even more comprehensive list may be helpful.

Suddenly you have a very long list of great lenses to choose from! There are a couple more things to take into account, however.

When you are shooting, it is best to focus your shot with the lens aperture wide open. That means that when most lenses are “at rest” they are all the way open. Older lenses have a mechanical link to the camera, either a pin or a lever that is activated before the shutter releases, that closes the aperture down to your selected value.

Obviously modern electronic cameras lack that linkage. However, most lenses also have a button on the side of the barrel that closes the aperture. The original intent was to allow the photographer to get a better feel for the depth of focus they would be getting for the shot, but you can hold that down when you fire the shutter and get the f-stop you want. Pushing sideways on the lens is a great way to get unwanted camera shake, however.

As an alternative, you can look for lenses with “preset” in the description. These are lenses that allow you to disable the aperture mechanism (or sometimes these lenses just don’t have that mechanism). My Mir-42 is a good example of one of these; I can get the focus wide-open and then flip the switch on the side to put it into preset mode. Once that’s done I can shoot normally.

So now you have a couple of keywords to look for when searching for old manual-focus lenses. You know which lenses will physically fit on your camera, and you know which ones will be easier to work with. That won’t help you figure out which lens you should buy, but it will sure rule out a bunch you should not.

____

* yes, literally.